Awareness, Cost, and Access: Unlocking Health Insurance Inclusion in Nigeria

Transforming Healthcare for Millions Through Smarter Systems

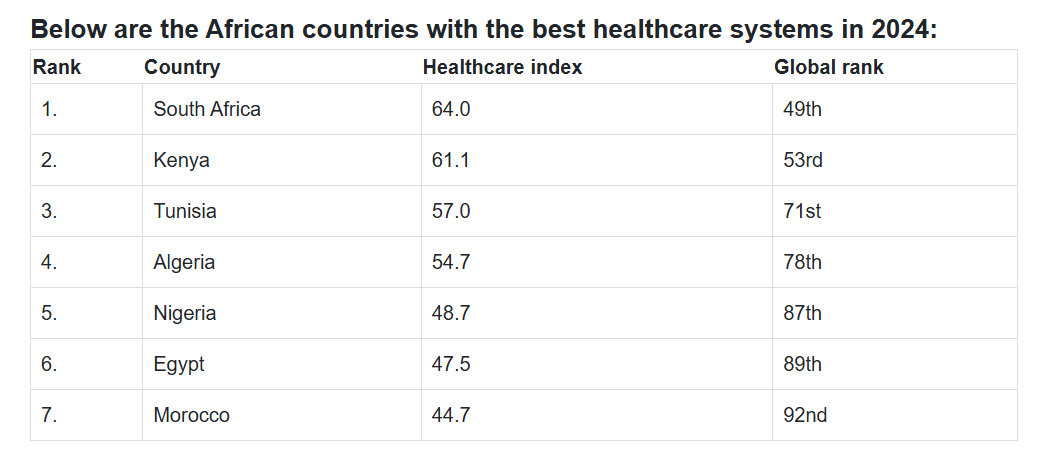

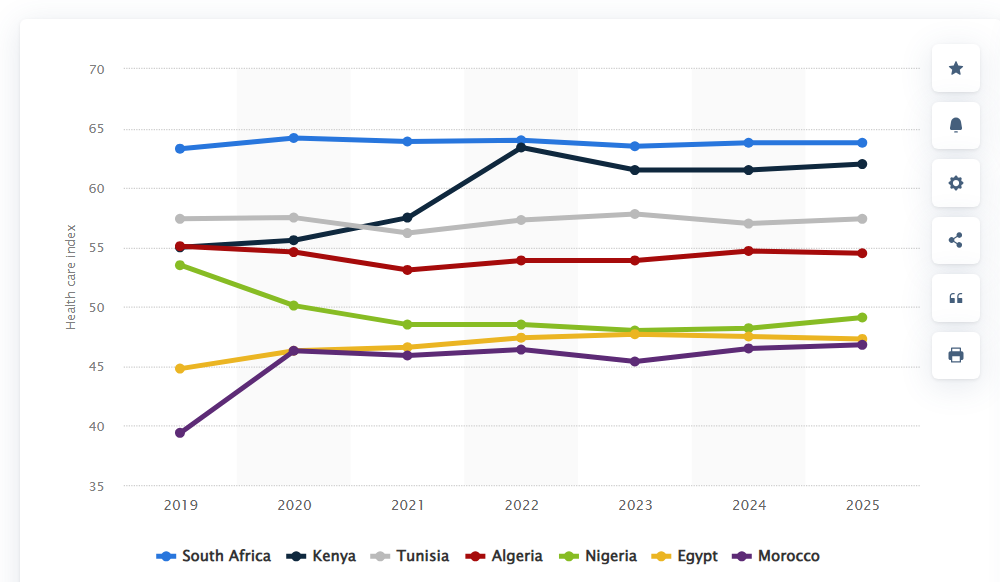

In Nigeria, the phrase "health is wealth" carries a bitter irony for millions. For many, accessing quality healthcare feels like a luxury, not a right. Picture Mama Ifeanyi, a market trader in Lagos, struck by a fever. Instead of heading to a hospital, she visits a local chemist, where a salesperson—without medical training—recommends a drug after a brief chat. A few days later, she’s back on her feet, praising the chemist to her neighbours. But what Mama Ifeanyi doesn’t know is that her reliance on out-of-pocket payments and unregulated remedies is a gamble with her life. This is the reality for millions of Nigerians, where out-of-pocket healthcare spending accounts for a staggering 75% of health expenditure, one of the highest rates globally. Nigeria’s healthcare system lags behind African leaders like South Africa, which scored 63.8 on the 2025 healthcare index, and Kenya, with 62 points, both reflecting robust systems. Nigeria, by contrast, ranked 87th globally in 2024, a stark reminder of the work ahead. The path to change lies in fixing three critical barriers: awareness, cost, and access.

The Crushing Weight of Out-of-Pocket Payments

Why do so many Nigerians, like Mama Ifeanyi, bypass hospitals? It’s not just habit—it’s economics. A three-day stay in even the smallest clinic can cost upwards of ₦50,000, a sum that is almost at par with Nigeria’s minimum wage of ₦70,000 per month (as of 2024). Nigeria spends just $10 per person on health annually, far below the $86 needed for universal health coverage, according to global health standards. The result? People turn to self-medication or street pharmacies, risking misdiagnosis and complications. A 2021 Dataphyte report revealed that 97% of Nigerians lack health insurance, leaving them vulnerable to catastrophic medical bills. In 2018, Nigeria ranked third globally for out-of-pocket health spending at 76.6%. These numbers aren’t just statistics—they’re stories of families pushed into poverty by a single hospital visit.

I’ve seen this firsthand. A friend’s mother delayed treatment for a chronic condition because she couldn’t afford the hospital’s deposit. By the time she sought care, her condition had worsened, requiring costlier interventions. This isn’t just a personal tragedy; it’s a systemic failure. Health insurance could have saved her years of suffering, but she, like many, didn’t know it was an option. This brings us to the first hurdle: awareness.

Awareness: The Missing Piece of the Puzzle

Health insurance in Nigeria suffers from an awareness crisis. A 2025 survey by Dean Initiative found that 1,556 out of 4,188 young Nigerians had never heard of health insurance. That’s over a third of respondents, and the numbers are likely worse in rural areas. Without understanding what insurance is or how it works, people like Mama Ifeanyi see hospitals as predatory, not protective. They don’t know that for as little as ₦15,000 a year—the cost of the Lagos State Ilera Eko Standard Plan in 2024—they could access quality care without breaking the bank.

To change this, we need to take a page from Nigeria’s marketing giants. Companies like MTN and Coca-Cola plaster their brands across billboards, radio jingles, and market stalls. Fintechs like Opay and Moniepoint turned sceptics into digital banking users by embedding agents in communities and simplifying onboarding. Health insurance needs the same energy. Imagine Ilera Eko stalls in every major market, with agents explaining plans in local languages, working through trusted community leaders like the Iya Oloja (market women’s leader). These leaders could champion enrolment, ensuring no one resells plans for profit—a risk that must be tightly monitored.

Social media campaigns, tailored to Nigeria’s youth-heavy population, could also bridge the gap. Short, relatable videos showing how insurance saves money and lives could go viral on platforms like TikTok and Instagram. Community outreach, backed by government and private partnerships, could bring these messages to remote areas. As Semiye Michael of Dean Initiative said, “We need to challenge existing policies and explore new ways to ensure health services are accessible.” Awareness isn’t just education—it’s empowerment.

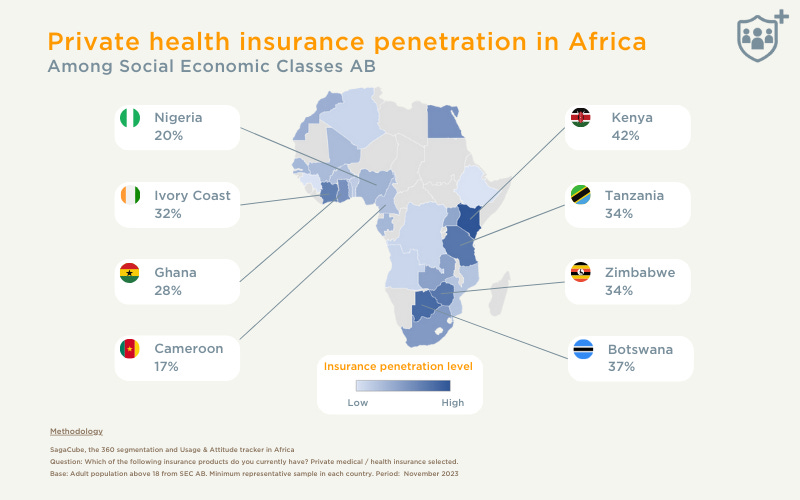

Kenya offers a powerful example. A 2023 survey revealed Kenya had Africa’s highest private health insurance penetration rate at 42%, driven by a competitive insurance market and innovations like M-Tiba and mTek-Services. Mobile-based solutions, rooted in Kenya’s Mpesa ecosystem, have simplified access to insurance, making it as easy as a few taps on a phone. Nigeria, with its thriving fintech scene, could emulate this, leveraging platforms like Opay to push insurance awareness to the masses.

Cost: Busting the Myth of Unaffordability

The second barrier is cost, or rather, the perception of it. Many Nigerians assume health insurance is a luxury for the elite. A 2024 NOIPolls survey found that only 19% of adults have health insurance, with high cost cited as a major deterrent. But here’s the reality: basic plans are more affordable than most realise. Some HMOs offer coverage for as low as ₦300 per week—less than the cost of a daily meal for many. The National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) plan, which covered gynaecological services and surgeries, cost ₦15,000 annually in 2024, rising to ₦38,000 in March 2025. For women of reproductive age or those with chronic conditions, this is a lifeline.

The problem? These prices aren’t widely advertised. Visit the Ilera Eko website, and you’ll struggle to find clear pricing for plans. Transparency is critical. If we’re serious about inclusion, HMOs and state schemes must display plans, prices, and benefits upfront, just as e-commerce platforms list products. Burying costs breeds mistrust and confusion. Imagine a world where every Nigerian knows they can pay ₦15,000 a year for peace of mind—wouldn’t that change the conversation?

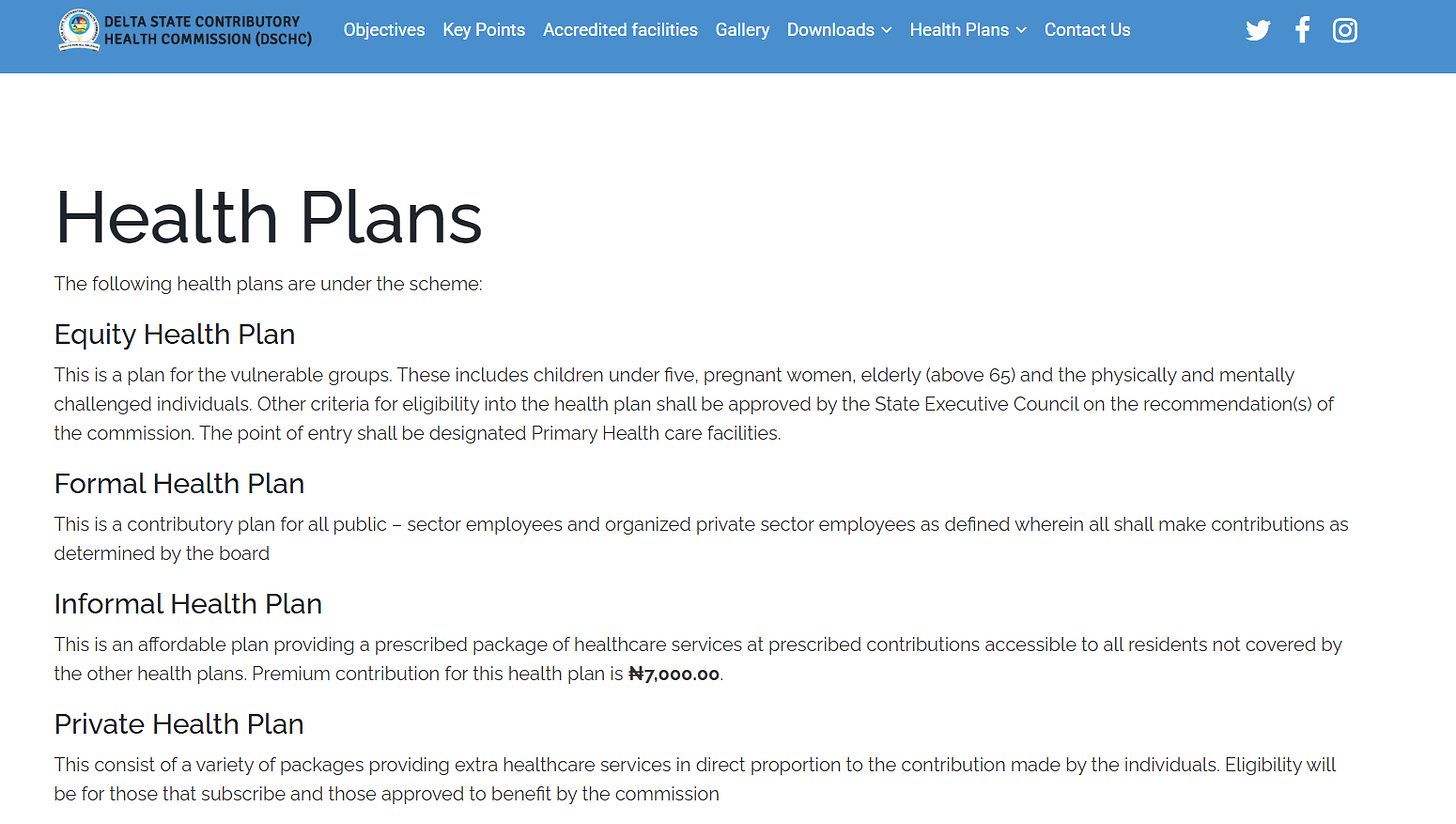

P.S.: Almost all of the states in Nigeria do not have a clear plan and pricing on their websites. See some examples below.

Kenya’s success underscores the power of affordability. Its competitive insurance market has driven down premiums, making coverage accessible to 42% of the population, compared to Nigeria’s 19%. Botswana follows at 37%, while countries like Guinea and Ethiopia languish at 9%. Nigeria can learn from these leaders by fostering competition among HMOs and ensuring prices are visible and reasonable.

Beyond transparency, affordability can be boosted through innovative financing. Dean Initiative’s survey recommended health taxes on tobacco, alcohol, and sugary drinks to fund subsidies for vulnerable groups. Expanding the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) from 1% to 2% of Nigeria’s revenue could also lower premiums. These aren’t pipe dreams—they’re practical steps other countries have taken to make healthcare accessible.

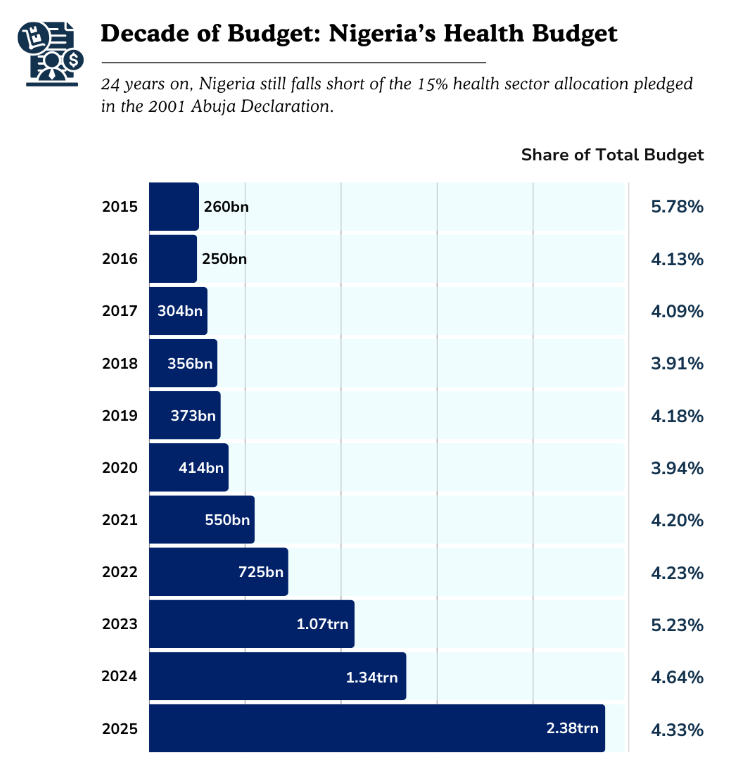

Access: Bringing Insurance to the Last Mile

Even with awareness and affordable plans, access remains a choke point. Health insurance feels like a premium club because distribution is broken. Nigerians don’t know where to sign up, and when they do, they face long wait times at understaffed hospitals. Nigeria’s doctor-to-patient ratio is a dismal 1:10,000, far below the World Health Organisation’s recommended 1:1,000. A 2025 budget analysis by Dataphyte showed health spending at less than 5% of Nigeria’s budget, against the WHO’s 15% benchmark. This underinvestment cripples access to care, even for the insured.

Fixing access requires a two-pronged approach: seamless enrolment and robust healthcare delivery. On enrolment, let’s learn from fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies. Dangote and BUA cement reach Nigeria’s deepest villages despite logistics challenges because they’ve mastered last-mile distribution. Health insurance can do the same. Set up enrolment kiosks in markets, churches, and mosques. Partner with fintechs to integrate insurance payments into mobile apps and POS like Opay, Palmpay and Moniepoint, where users already trust digital transactions. Kenya’s M-Tiba platform shows how mobile tech can streamline enrolment, a model Nigeria could adapt to reach millions.

On healthcare delivery, we must address hospital wait times and quality. South Africa and Kenya lead Africa’s healthcare index because they’ve invested in facilities and staff. Nigeria’s 87th global ranking in 2024 reflects underfunded primary health centres (PHCs) and overworked doctors. Training more healthcare workers and equipping PHCs is non-negotiable. Dean Initiative’s survey called for youth-friendly training for providers, which could reduce stigma and encourage uptake. Expanding PHC networks, especially in rural areas, would ensure insured Nigerians can access care without travelling hours.

Designing a Healthier Future

The rise of out-of-pocket payments isn’t just a symptom—it’s a signal that Nigeria’s healthcare system needs a redesign. Awareness, Cost, and Access aren’t isolated issues; they’re interconnected pieces of a puzzle we can solve. As a marketing and product professional, with experience driving insurance products (Curacel 😊), I believe the solution lies in human-centred design. We must meet Nigerians where they are—physically, financially, and culturally. That means taking insurance to the streets, making costs clear and affordable, and ensuring hospitals are ready to serve.

Mama Ifeanyi shouldn’t have to choose between a chemist’s guess and a hospital’s bill. With the right reforms, she could walk into a clinic, flash her insurance card, and get quality care without fear. Nigeria has the tools to make this happen: a vibrant population, a growing fintech ecosystem, and a legacy of community resilience. South Africa and Kenya show it’s possible—Nigeria can join them.

Let’s start the conversation. How can we bring health insurance to every Nigerian? Share your thoughts, because together, we can design a future where health truly is wealth.